Category: News

Colin Griffin – Walking the Walk

“Colin Griffin has no regrets about taking a step back from his athletics career last month. But now he hopes the sport can take a giant leap forward in how it deals with elite competitors.

On the way to meet you, he got a call from a friend. They talk most days, like you may do with your best friend, only yours isn’t a world champion. Colin Griffin’s is.

For more than a decade now Rob Heffernan has been a contemporary, something of a rival but mostly a friend. When either of them was struggling, the other was there to hear and help the other out.

When Heffernan awoke the morning of the 2012 Olympics 50km race, Griffin was in the other bed, his roommate for most major championships.

Yet when Heffernan finally had his moment in time last August, shuffling into that stadium in Moscow and grinning over the finishing line, Griffin wasn’t there.

Instead, he was back home, in a Dublin apartment, on Twitter like some kind of parachuted commentator explaining to half the country the nuances of just how his old friend had won.

He won’t lie, it was a surreal experience: Rob finally winning a big one and him on a sofa back home. He was delighted for Heffernan and was there at the airport to greet him upon his return, but while he hoped it ignited droves of kids and athletes to take up or step up in the sport and event he loves, it didn’t spark anything in him to give it another go.

The year 2013 had been one of the most testings in a very testing career. Too much time was spent challenging administrators rather than fellow competitors on the road. The week before Christmas he announced his decision: he was putting his athletic career on hold. At 31 he was still too young to close the door on an event that favours the older athlete, but he couldn’t keep putting the rest of his life on pause either.

“Being a full-time athlete for all those years is an intense lifestyle. When things go well and you make a breakthrough it’s brilliant, you experience this euphoric feeling. When things don’t go well you are challenged.

“I’ve probably had more of those challenging moments than those euphoric moments, especially in the last couple of years. And that does take its toll. There are only so many times you can put yourself out there.

“The reality is very few athletes make a living out of the sport. Even major championship winners like Rob and Derval [O’Rourke] have no guarantees and little security, so someone like myself further down the chain can only do it for so many years. It’s like, I love this sport but can I really keep justifying doing 200km a week and all those hours training in something that doesn’t bring in a sustainable income?

“I’m 31, in a long-term relationship and you want to be thinking ahead. I didn’t want to be 35 with no pension fund or real experience in a career outside athletes.

“I didn’t want to close the door on competing for good and then have regrets in 10 years’ time, but I want to get my business developed. That’s going to be a 24/7 job. So is being an international athlete so putting the two together is just not feasible.”

We’re talking in a café on Canal Dock in Dublin. He’s from Leitrim, then studied and trained in Limerick for years but moved to the capital last year just like his Belfast-born girlfriend, Clare, did as well. This is where he plans to have his own business: an altitude training gym in the biggest population centre in the country.

He’s been working on the side in that area for a few years now but after the Olympics and the ordeal of last year, it’s athletics that he’s now pushed to the margins.

You may well not know what happened to Colin Griffin in London, how hard it was for him to make it there in the first place. Or maybe you do and have had a cursory look at his career. Constantly being disqualified in races because of a questionable technique, including London. Appealed a decision by the chief of Athletics Ireland that he shouldn’t receive any Sports Council funding. Just yesterday in the Irish Examiner pronouncing athletes should have their own representative body along the lines of the GPA.

And from that remove maybe you’ve come to some conclusions. That he’s an agitator. Too opinionated, too old, too limited and too much hassle to invest in or care about.

It’s not like that though. He’s opinionated alright, but it’s always a cool, calculated, rational, sober view he offers, without a hint of the chippiness or outrage or sarcasm.

So when he says that Irish athletes should have a GPA-like service, that Irish athletics doesn’t respect its coaches or athletes enough, that there should be a national head coach for each athletic discipline, it’s worth listening to. He may be no Keane or Derval or Rob Heffernan but he’s experienced, intelligent, insightful and sensible. He’s learned a lot from his career in athletics. Athletics, and not just athletes, have a lot to learn from him.

London was supposed to the pinnacle of that career in athletics. And it so nearly was. Once he qualified for it at the last possible attempt in a race in a Russian town called Saransk, he promised to enjoy the lead up as well as train hard. He did both and when he and Heffernan awoke that morning of Saturday, August 11, he felt it was going to be his day of days. Laura Reynolds, whom he coaches, was competing later that afternoon in the women’s 20k. It was his parents’ wedding anniversary. Speckled everywhere along the route were well-wishers from Ireland. “Up Leitrim!” “Go on, Colin!” ‘Come on, Ireland!” There were goodwill and energy everywhere.

At 25k he picked up his first red card, and then at 35k when he lost a group, he picked up a second, his unorthodox technique all the more conspicuous due to his isolation and height. Walking is a bit like baseball – three strikes and you’re out – but when Griffin rejoined a group that were all vying for a top-16 spot, he was back on track.

“I was attacking the race like this was what I always wanted. I was on the course for time five minutes better than my personal best. I was having the race of my life.”

And then just like that, it was all over. At the 38km mark, he looked up at the big screen and saw the third dot alongside his name. A judge stepped out to confirm that once again he didn’t have one of his feet in contact with the ground. It didn’t matter that it was only a judge’s opinion; in walking, a judge is a judge.

The rest of the day was a mix of emotions. He gathered and braced himself for the awaiting media. He urged Rob Heffernan on. Then from the drinks table, he would urge Laura on to a top-20 finish, a remarkable achievement for an athlete of her inexperience. The next morning it hit him. He didn’t know if he wanted to compete at this level anymore.

A few months later he and Clare headed off to Australia to help clear his head. If anything it became more confused over there. The day they arrived he received an email from Athletics Ireland high-performance director Kevin Ankrom, informing him he wasn’t going to be forwarded for any Sports Council funding for 2013.

“I met the criteria for that year. So while I understood he was entitled to his recommendation and that I had no automatic entitlement to be carded, I felt I at least should have a chance to appeal. I mailed him back but didn’t hear anything for another month until the Sports Council deadline had passed. I was top 16 in the world. I met the A standard. Yes, I was disqualified at the Olympics but I had qualified for the Olympics (without any funding in 2012) and felt with the right support I was capable of a big performance on any given day. I felt the glass was half full rather than half empty, whereas instead I was perceived as a liability, not worthy of investing in.

“That’s the way they put it: you’ve received a cumulative €90,000 in funding since 1999 and the investment isn’t working out. I would say to that I’ve learned a lot over those 13 years. I’ve become a coach. I’ve been able to bring altitude training back to Ireland and while I’ll hardly transform the economy I will be creating employment. All these little things add up as value for the taxpayers’ money. But they don’t see value in that.”

One member on the Athletics Ireland board did. Liam Moggan agreed that Griffin was entitled to an appeal process and after much wrangling, he was granted one in April. It was recommended that he should receive a grant of €6,000 for the year but even after Ankrom and Griffin shook on that there would be disputes about how it was distributed. In July Griffin called Ankrom to inform him of his displeasure, and as he puts it, “the conversation was less than friendly”.

For Griffin that was his breaking point, not London. Last March after he’d returned from Australia he’d returned to London for a few days, strolled around The Mall and Constitution Hill which the 50km walk route took in. He also popped over to Strafford where the Olympic park and village had been. Now it was like they had never been there. London had moved on from the Olympics. It was time he did as well. After that bit of closure, he was fine about London. But from his wranglings with Ankrom, he wasn’t ready for Moscow. Time and energy that should have spent training and competing had gone into fighting the system that was supposed to be supporting him. By the autumn he had his mind made up he wasn’t going to compete in 2014.

He still works out every day: he either goes for a walk, a run or the gym out in Santry. He still coaches Laura and other walkers and is hugely conscious of what support structures – or lack of – might be out there for them. Laura is walking quicker times than Olive Loughnane and Gillian O’Sullivan were at her age.

They each won silver at the world championships. Yet she didn’t hear from Ankrom for over four months after the world championships. There is no head coach for walking in Ireland. Here is a sport where Ireland have won their last three world championship medals in. Without any real structure or culture in the event.

What would it be like if we had? “In this country, you have athletes who are trying to live like professionals. You have physios and sports scientists who are professional. But then all our coaches are voluntary. I know from coaching Laura there isn’t enough respect for coaches. There’s very little communication between the federation and the coaches.

Laura hadn’t heard from Kevin until the Monday after Christmas when he rang to tell her what her funding was for 2014. He’s supposed to be her performance manager. He hasn’t communicated with me – and I’m her coach. It turns out me and her physio and doctor sat down in September and outlined key areas such as injury prevention and strengthening her immune system, so we’ve been working away on that, and being proactive.

Other structures need to be put in place as well. The carding scheme he feels can sometimes inhibit an athlete as much as aid them. Sometimes you might need to take a step back to go two forward – Griffin himself would love to have broken down his faulty technique for a couple of years – but the need to get that next result to get the next bit of funding didn’t allow that. Less of a squeeze and more of a long-term investment plan would be better for everyone, he feels. As would a GPA-like representative body.

“If you talk to a lot of athletes they’ve often felt isolated and exposed and having to fend for themselves. At the moment athletes are just commodities. You’re only as good as your last race. You can be very easily disposed of. If you have one or two bad years you can go off the radar and be neglected. Then your career could be over at 30 and there’s nothing there to actually help you regarding advice on finance or career development and so on. Mental health is another area in a high-performance sport that hasn’t been looked at properly.

“You can get sucked into so many battles outside the track such as selection or funding with no one else able to represent you and energy you should be putting into your preparation and performance is being consumed elsewhere.”

These days a lot of his energy is going into developing a business (see altitudecentre.ie). Griffin has been fascinated by altitude training ever since 2007. He was training for his first 50km race so he trained at altitude in South Africa and upon his return availed of an altitude tent. A few months later in Slovakia, he won that first 50km race, setting a national record. He’d been able to train better, faster, for longer. He became so intrigued by this facility he visited the Altitude Centre in London and took on their Irish franchise. He made a proposal to University of Limerick to build Ireland’s first altitude house along the lines of the one at the Australian Institute of Sport. So they built and they have come, from international athletes to international rugby players to inter-county GAA players.

The next stage is to make his services more mainstream, less elitist. To have it just like your normal gym, only that bit more intense and challenging.

It’s a risk, this business, he knows, but then he’s coming from a sport where constantly left himself open to failure. Did he fail? It doesn’t sit well with him when people continuously remind him he’s an Olympian, something that can never be taken away from him.

“That doesn’t sit well with me at all. I don’t have a finishing performance to my name. I have to accept that for now. Do I have regrets? I didn’t do well enough at major championships. But I enjoyed my career. I still loved training, competing, learning. That has helped develop me as a coach probably more than as an athlete.”

It’s not that devoting so much to walking wasn’t worth it, so. It’s just that it’s not worth doing anymore – at least for now.”

| For the full article in The Irish Examiner |

New Consultants at SSC

SSC are delighted to welcome the following to our team.

Ruth Delaney

Ms Ruth Delaney is a consultant orthopaedic surgeon and shoulder specialist.

Professor Cathal J Moran

Professor of Orthopaedics & Sports Medicine, Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon.

Mihai Vioreanu

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon

Michael Donnelly

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon

Barry J Sheane

Consultant Rheumatologist

E Kathir Tamilmani

Pain Management Consultant

‘Knee Pain – It could be your Iliotibial Band’

SO, THE ANATOMY IS SIMPLE?

WHAT CAUSES IT?

Many reasons: an increase in mileage, more hill work, more speed work and a change in stride length or just fatigue. Your physio, therapist, or doctor will likely lie you on your side and let your leg drop behind you with a flexed knee to find the sore spot. We usually inject some local anaesthetic into the fat pad to confirm it before looking at your running style.

WHAT WON’T FIX IT?

Well, no amount of needling the length of the fascia, orthotics or foam roller up and down the leg will make much of a difference and certainly not changing your runners! But you can deep tissue massage the glutes, get stronger in a single leg landing jump and change your running kinematics. We often see ( Fig2) a lack of glut control in the stance phase, causing the hip to drop and the leg to rotate, combined with too long a ground contact time and a lot of knee flexion. Cross over gait is also common, like running as a catwalk model.

SO WHAT SHOULD YOU DO?

• Good Hip extension and landing drills in the gym. Stiffer running gait (less knee flexion), and reduce the time on the ground…think about running like a piston.

• Deep tissue massage/sliotar to the TFL

The authors from the UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic carried out original research into the function and management of ITB at the University of Melbourne, published in Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 2009: ‘Iliotibial band syndrome: an examination of the evidence behind a number of treatment options’.

| Click here to download PDF of the article in full. |

SSC launches its new Lactate Testing services

At the UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic, we individualise the lactate test to ensure it meets the athlete’s requirements, such as their current training status and the race distance they are preparing for. The lactate threshold and subsequent prescribed training programme for a 5km runner differ from that of a marathon runner.

At the UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic, we individualise the lactate test to ensure it meets the athlete’s requirements, such as their current training status and the race distance they are preparing for. The lactate threshold and subsequent prescribed training programme for a 5km runner differ from that of a marathon runner.

|

‘Welcome news for groin and hip sufferers’

“Often athletes have been advised to rest for anywhere between four and six months and then gradually build it back up again. So, when you’ll offer them nine weeks, they’ll nearly take the handoff you. Also, nine weeks is very much the average of what we’re looking at. So, there are athletes that are quicker, athletes that are slower.”

King believes the treatment of hip and groin injuries has suffered from common misconceptions and, subsequently, athletes have struggled through a misguided rehab, sometimes not recovering properly.

“It’s an area probably poorly understood and, as a result, poorly rehabilitated and treated. It goes back to groin pain being thought of very anatomically. Someone has a pubic problem or a groin or a ductor issue and therefore, that area of the body is thought of as the problem. Actually, it’s very much the victim. Groin pain is to do with the way you’re moving and you can’t cut or inject your way out of a problem like that.”

With a relentless stream of athletes visiting the SSC team in Dublin 9 complaining of the same injury, King believes many have been set on the wrong path by age-old misdiagnosis.

“We’re treating approximately 40 new groin patients per week in the clinic so when you’re seeing that volume of athletes coming through with the same problems, you develop a sound understanding of the mechanics driving it and the common pitfalls. For example, the athletes being told that resting the groin will make it better. But rest doesn’t change your movements so as soon as the athlete returns to the level they had been training at before, their symptoms will come right back. Then, they’ll feel they need surgery to correct the groin problem.”

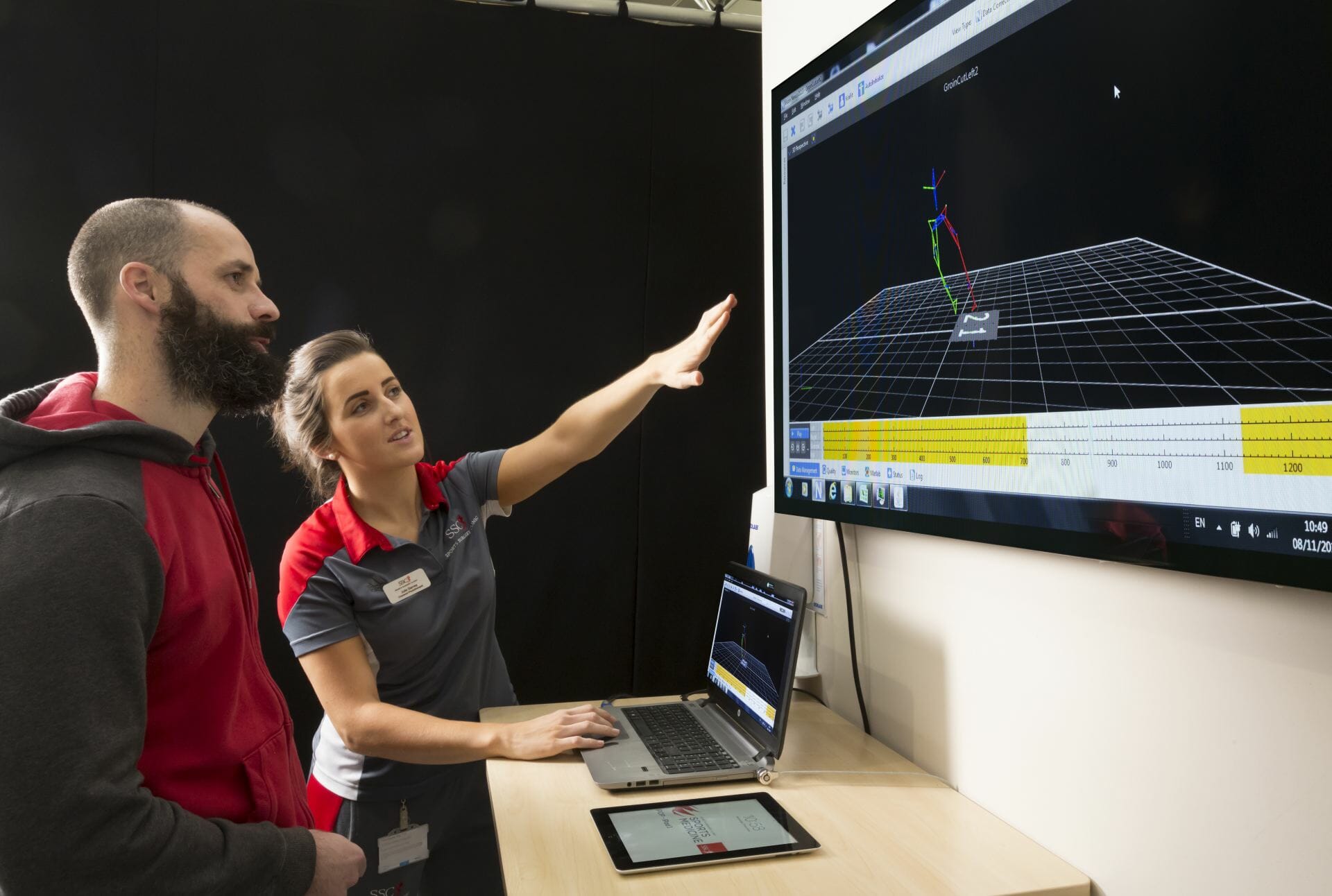

The SSC research into the groin and hip injuries have used 3D biomechanics to intensely study the body’s movements, giving a greater understanding of where an athlete’s problems are stemming from.

“The rehabilitation programmes are individualised. Rather than giving everyone the same, the 3D biomechanics drive the athlete’s own individual deficit and are specific to where their errors are and that’s what allows us to get more efficient. We try and break the programme into three broad segments. One is your single-leg control — your ability to use your abdominal muscles, your hip-flex to stabilise you on one leg and then taking that through squatting and hopping and landing patterns. Phase two would be your linear running pattern — how you run and how efficient your running mechanics are. Level three is your multi-directional work — how efficient you are cutting, turning and evading. Different athletes are better at different parts. Some may have very good linear and could have very poor multi-directional so it varies all the time. But, focusing on what can be generally applied to the sporting populations, if you’re working on operating those three levels, you’ll be a better athlete and your injury rate will be lower.”

King also thinks the biomechanical analysis ensures athletes become more invested in the entire process. They can see what’s wrong with how they’re doing something as well as the potential benefits once they make the requisite corrections.

“If we’re basing biomechanics on how quickly you recover, then how quickly you can improve your biomechanics will ultimately dictate how speedy your recovery is. What we’re saying to the athlete is ‘the way you’re moving is driving your groin pain. The quicker you change the way you’re moving, the quicker your groin will improve’.

Where the real buy-in is long-term with this is that athletes understand when you show them the 3D mechanics and show them the animations. They can see how much quicker they’re going to be when their mechanics are efficient. So, very quickly, the conversation goes from ‘how do I get back from groin pain’ to ‘how can I become a better athlete than beforehand?’”

Perhaps most worryingly, King feels groin and hip injuries have been misunderstood at all levels. For him, many in the sports injury field have been looking for the answers in the wrong place.

“I think sports medicine, in general, has been approaching groin pain the wrong way around.

“They haven’t been looking at the overall mechanics and, regardless of what level of sport you’re operating at, there has been a poor understanding of the biomechanical factors that drive groin pain and the steps you need to take to resolve it permanently.”

The good news is that the UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic are doing things differently.

| This story appeared in the printed version of the Irish Examiner Monday, May 19, 2014 |

‘A Joint Effort ‘

The first thing that catches your eye when you cross the threshold of Marian Richardson’s delightful home in Dun Laoghaire is a tiny, high-heeled Cinderella slipper lying on its side, looking lost. Judging from the slipper’s size, you might think Marian has tiny feet. But having suggested as much, she replies: “That’s not my shoe – it’s a doorstop!” Oh, dear. Already feeling embarrassed, I notice that Marian is wearing sturdy trainers easily a size or two bigger than the slipper. Yet more blushes.

When I meet her, Marian is supporting herself on crutches, having had recent surgery on her knee to fix a long-term problem. She hopes to be off them and inside a pair of high heels in time for her next birthday. And, given this doyenne of broadcasting’s track record when it comes to surmounting obstacles, I have no doubt she will turn up to the party the picture of elegance. And I’d bet she won’t be wearing flats. Marian’s troubles began long ago, mainly through playing sport as a child.”Over the years, I played a lot of tennis, rounders and, of course, I was always running for buses,” she says “I’ve always had dodgy knees, but, just over a year ago, after I got off the Dart, my knee went from under me. I had the most excruciating pain – it was even worse than childbirth. I went from being someone who could run to not being able to walk.” Following X-rays, her doctor diagnosed osteoarthritis (OA), which is caused by wear and tear on the joints, and affects about 400,000 people – mainly older individuals – across Ireland.

Next, Marian was referred to the UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic in Santry, in north Dublin, under the care of consultant orthopaedic surgeon, Ray Moran. “I’m one of those people who believe Ray is next to God,” says Marian. “He likes to treat OA conservatively, so we tried intense physio to see if it would ease the problem.” Jenny Branigan, who is the women’s national team physiotherapist at the Football Association of Ireland was drafted on to the case, but she discovered that Marian’s knee was too damaged for physiotherapy to be of any benefit. So it was back to Ray.

Having tried unsuccessfully to sort her out with a special injection into the knee, Ray decided an arthroscopy – a form of keyhole surgery used to treat the body’s joints – would be the course of action most likely to produce results. The operation saw two small incisions made in Marian’s leg – one to insert the arthroscope (a tiny surgical camera) and another that allowed Ray to scrape away damaged tissue inside the knee.

Experts hoped that, by cleaning out the joint, it would heal. It is a procedure that is successful for many people, but Marian was not one of them. Four months on, Ray came to the conclusion that there was no option other than a knee replacement. After a pre-operation checkup to make sure she was well enough for surgery, Marian met with the anaesthetist, who suggested an epidural. While this is a localised form of pain control, it also knocks out the patient.”I wasn’t sitting up having a cup of tea,” jokes Marian. “In actual fact, I have no recollection of the event, which was pretty hardcore surgery.” When she woke up, her feet were encased in massage bootees and “elegant anti-thrombosis stockings”.While Marian was in a good deal of pain, medication was kept to a minimum. But, with a little work, she was soon back on her feet. “The day after your surgery, the physio comes and you’re out of bed,” Marian tells me. “The staff really make you feel you can do it. You can’t leave the clinic until you can bend your knee at an angle of at least 90 degrees. So for it to work properly, you really have to be diligent and do your exercises.”

Now on the road to recovery, the broadcaster stayed in the hospital another five days. A week after she was discharged, she returned to Jenny for physiotherapy. Her treatment plan included “walks” in the swimming pool and riding a static bike at home.

Probably the biggest problem for Marian was not the pain itself, but the physical inaction and the resulting boredom. “I felt I could do very little,” she says. “Some people go to a convalescent home, but I had my husband, Michael Good [deputy managing director, News and Current Affairs at RTE ], my two sons, their partners and my gal pals to help me, and they were all great. “Still, when you’re used to running around, it’s hard to sit about doing nothing. After all, it isn’t cancer and you’re not sick. I took Aine Lawlor’s advice and read a lot of trashy novels.” Marian overcame her boredom by reminding herself it was for the short term, by telling herself she would eventually get past the pain and frustration that inactivity caused her. She took inspiration from the trials previous generations had faced, all the while remaining mindful that her quality of life would be much better at the end of this difficult episode. “Our mothers and grandmothers were in terrible pain [when they had similar problems], but now we have total joint replacement,” Marian says. When I spoke to her, the journalist was looking forward to a well-earned holiday in Italy and was planning to bring out the heels and pile on the bling. And she deserves it, too – Playback with Marian Richardson, her Saturday morning show, has become extremely popular. You might imagine there is a team of researchers behind the programme, but you would be wrong: it is just Marian and no one else. “It’s a one-woman operation,” she says. “You look and listen, and then decide on the clips. After the show, I will be gearing up for the next week’s show.”

It’s not just that Marian’s had a terrific career – it started when she was 14 with a part in a production of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck, then moved on to presenting, producing and reporting on a host of topics from the fall of the apartheid regime in South Africa to the inauguration of Barack Obama as US president – it’s that she’s a true all-rounder, a supremely gifted broadcaster and, if you’ll forgive the pun, a lovely woman to boot.

| UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic, Santry Demesne, D9, tel: (01) 526-2000 |

SSC Sports & Exercise Medicine Team present at the 2014 Football Medicine Strategies Conference in Milan

UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic had a strong presence at the recent Football Medicine Strategies annual conference in Milan, Italy.

Members of the Sports Medicine team gave oral presentations on a range of topics including:

‘The role of strength and conditioning in reducing injurious loads’ by Dr Andy Franklyn Miller

‘The biomechanics of change of direction cutting’ by Dr Brendan Marshall and Neil Welch

‘Movement efficiency in Gaelic Games players’ by Enda King

‘The relationship between isokinetic strength and landing biomechanics’ by Marit Undheim

All presentations were well received and stimulated much discussion among the 2259 participants from 71 nations around the world.

| More details on the specific presentations given by our team can be found by clicking here. |

‘Should you consider a Knee Replacement Operation’

Margaret Mullett, the chairperson of the Irish Haemochromatosis Association, has had two knee replacement operations – one in June 2012 and one in September 2013. While it took a bit longer than she expected to recover from the first operation, she is very relieved to be pain-free and can now enjoy 45-minute walks “around the block” near her Dodder home.

Margaret decided to have her knees done because of pain and mobility problems due to arthritis and osteoporosis.

“My left knee troubled me first,” she says.

“I was finding it difficult to go up and down the stairs and, in spite of physiotherapy and a day-case arthroscopy (keyhole surgery to try and repair the damaged joint), it became clear that a total knee replacement was necessary.

“I did the exercises that are recommended before the operation in order to strengthen the knee and then had the operation done three months later in the Santry Clinic under general anaesthetic.

“By September it was my son’s wedding and I was making progress and only using a stick some of the time.

“Soon after that, however, my right knee started to act up so I had that operated on in September 2013. Thankfully, my recovery at that time was much quicker. I had physiotherapy and swam in a heated saltwater pool which is good for recovery.

“Now I have no pain, which is a huge relief. I’m delighted that I’m able to enjoy a walk again and that stairs aren’t a problem now. While I am still wary of falling if the weather is windy or the ground is wet, I am very glad to have had the operations done.

“Many people I know who have had knee operations have been mobile after six weeks, but it depends on how bad the knee is. What I would say to anyone going for the operation is to have patience and follow the advice. It will be worth it. I know that I wouldn’t be walking around pain-free if I hadn’t.”

Surgeon’s view

From a farming background, Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Denis Collins, wanted to be a vet but changed his mind at the last minute.

“I thought being a vet would be a hell of a tough life, so I opted for medicine instead,” he says.

“Orthopaedics* was the only area of medicine that really interested me though. Maybe it’s because I have a practical, mechanical kind of mind. As a doctor, I find that it’s always easy to talk to farming patients about joint replacements because, as a group of people, they know what a bearing is,” he says.

Denis Collins is based at Beaumont Hospital and UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic, Santry and operates to solve three kinds of knee problems.

“The majority of operations would be done because of degenerative arthritis,” he says. “Osteoarthritis, usually in people in their late 50s, is the most common reason for doing a knee replacement operation.

“The next more common reason would be the inflammatory type (of arthritis) like rheumatoid.

“Then there would be operations because of trauma in the past (damage to the knee through sport injury or accident). That injury, for example, loss of the shock absorber in the knee, would eventually manifest itself in arthritis.”

Denis Collins has operated on people as young as 20 and as old as 91.

“In younger patients, it can be the result of post-chemotherapy damage to joints after treatment for childhood cancers.”

Why surgery?

“The surgery is done to resurface the end of the thighbone (the femur) and the top of the leg bone (the tibia),” he says.

“This is where cartilage has worn away and where bumps and bony spurs called osteophytes have formed over the years.

“This is the result of the body trying to regenerate itself, but these osteophytes make the knee very rough and possibly deformed. The knee gets stiff then and you also have pain, so you have what we call lack of function.”

How it’s done

“We replace the worn cartilage with about a 9mm to 10mm metal coating (a pre-made, metal surfacing unit).

“Special instrumentation allows us to prepare special cuts at the end of the thighbone to prepare for and match the surface of the pre-made metal surfacing unit.

“The undersurface of the femoral component has a certain geometry and we create the same geometry at the end of the thighbone so the femoral component will fit on perfectly, like a glove. It is then grouted on with some cement.

“Likewise, you prepare the upper part of the tibia – the leg bone – for a special metal tray, then there is a plastic insert that goes in between the two and that allows the knee to move. The knee is a hinge joint and the constraint of the hinge – what controls the hinge – is your own soft tissue, your own muscles and ligaments.”

Are some operations more difficult than others?

“Yes. It depends on the degree of deformity and pre-existing trauma. Fractures may make the operation more difficult and sometimes we have to use other variants of knee replacements (units), but most of the time we can do it.”

“There is a perception out there that knee ops are less successful than hip operations. There is a little bit of evidence behind this in that the patient satisfaction scores for knee replacement operations are not as high as for hip replacements,” he adds.

“Hip replacement is one of those operations that have such a high success rate that it is a difficult yardstick to match. Still, knee replacement operations are nearly as successful. Generally, people do well after them and 90% are very, very happy.

“There are risks with every operation, but in a healthy person, or even someone who has underlying medical conditions that are well managed, it’s a very good operation.”

“The commonest complication that can occur afterwards is pain and there can be a difficulty with the rehabilitation in the early stages, including swelling and bruising.

“It’s a difficult process in the first six to 12 months following a knee operation, compared to a hip replacement. It is not more complicated from a surgeon’s point of view, but, for the patient, there’s a lot more involved in the rehabilitation process.”

Improvements

Improvements in the operation have happened in the past 20 years but are not totally related to the basic implant.

“If I showed you a 25-year-old design of it and one designed eight years ago, you probably couldn’t tell the difference,” he says.

“There are only subtle changes. The biggest differences now are:

- Our understanding of how to put the implants in.

- Improved instrumentation

- Better pre- and post-operative management of patients, for example, part of having a knee replacement operation is doing exercises before having it done.

- Better pain relief during and after the operation.

- Less swelling and bleeding (it is now unusual for a knee replacement patient to have a blood transfusion).

- Length of hospital stay has reduced from two weeks in the past down to four or five days.

Aftercare tips

Denis Collins wouldn’t advise anyone to stop using crutches quickly after the operation.

“Most people could walk without them after a few days, but I wouldn’t advise that because their muscles are still tender and sore. We don’t want people falling or hurting themselves.

“I would advise using two crutches and being able to walk properly that way, rather than using only one crutch and walking poorly with a limp.”

* Orthopaedics is the branch of medicine that deals with the prevention and correction of injuries and disorders of the skeletal system and associated muscles, joints and ligaments.

| For further information or to make an appointment with an orthopaedic surgeon email gp@sportssurgeryclinic.com or phone +353 526 2300 |

New research by the UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic will help athletes and GAA players recover from the groin and hip injuries in nine weeks, according to

New research by the UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic will help athletes and GAA players recover from the groin and hip injuries in nine weeks, according to