Why does Ireland have such a high rate of ACL injuries?

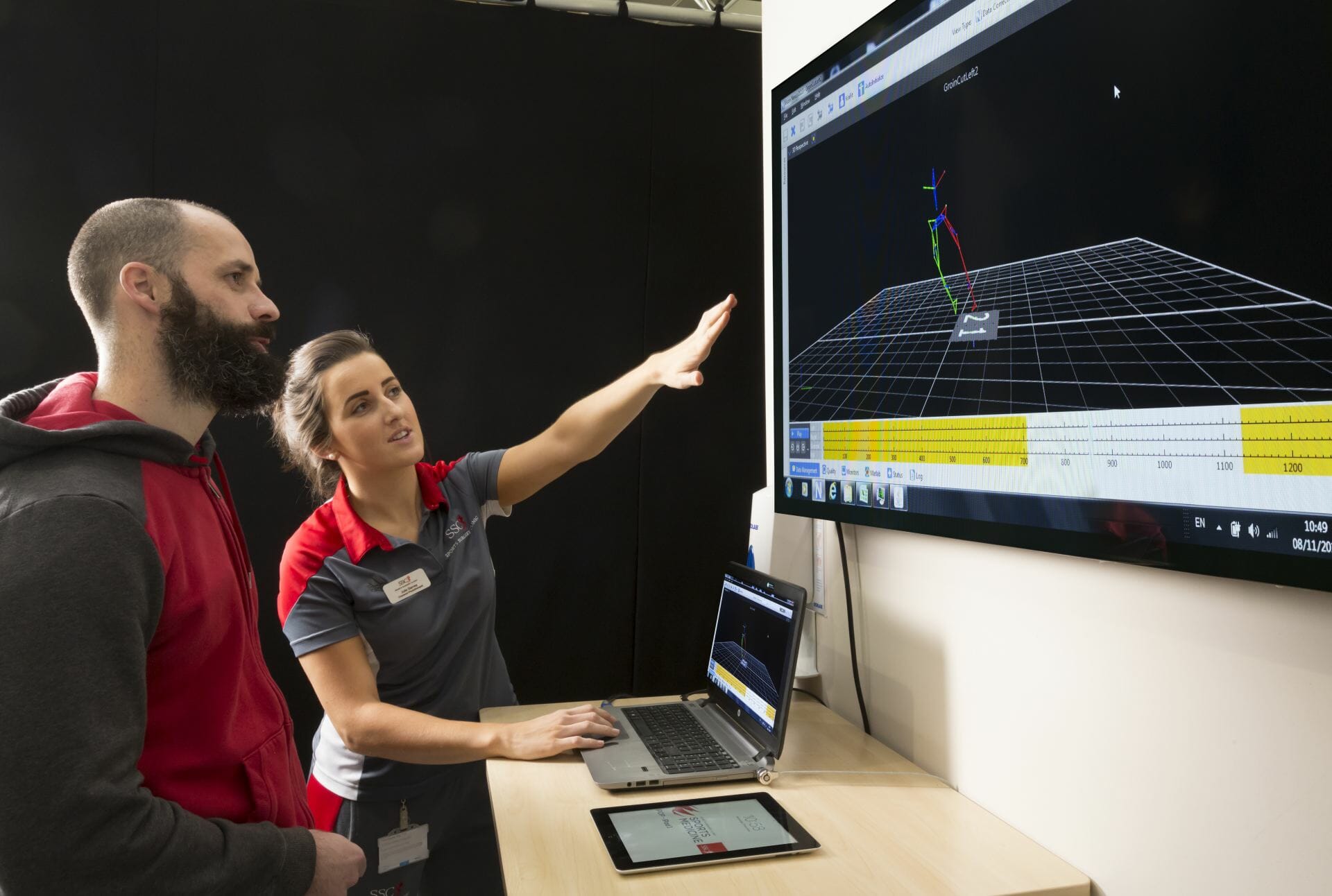

Professor Brian Devitt is a Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon at the UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic in Santry and a Professor of Orthopaedics and Surgical Biomechanics at Dublin City University.

This interview with Professor Brian M. Devitt was published on RTE’s Drivetime on 20th February 2023.

| For further information on ACL Injuries and Reconstruction or to make an appointment with an Orthopaedic Surgeon, please email info@sportssurgeryclinic.com |

The rate of Cruciate Ligament injuries in Ireland is among the highest in the world, which could be down to the types of sports commonly practised here. Brian Devitt is a Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon at UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic in Santry and also a Professor of Orthopaedics at DCU. He’s been researching this area, and he joins us now, you are very welcome Brian (BD)

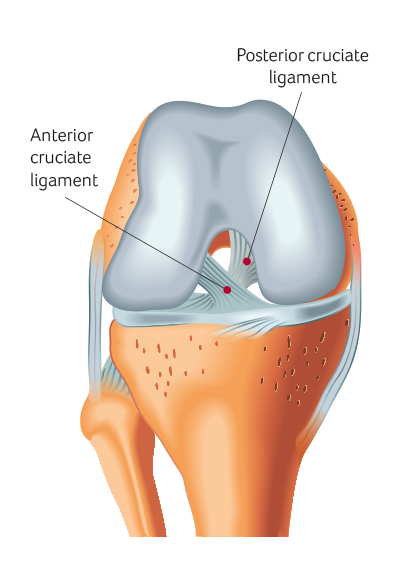

Just for those who don’t know what is the cruciate ligament and why is it so important?

BD: We have two Cruciate Ligaments, one is the anterior one at the front of the knee, and we also have the posterior one at the back of the knee.

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is the most commonly injured of the two, and it is only a 3.7cm ligament, but it is very important in sports because it controls rotation and stops our shin bone from moving forward in relation to our femur, side bone, so potentially it is a career-ending injury or at least it used to be anyway, but it certainly can cause a lot of damage in the knee when injured.

BD: It is surprisingly easy, and that’s the problem; it tends to happen with non-contact injuries. So it is not when someone is being tackled, for instance, or trying to evade an opponent but more as ‘pivoting’, which means moving quickly in one direction.

Seven out of ten times, it occurs as a non-contact mechanism.

BD: Yes, that is exactly right, a lot of those sports tend to involve a ball and particularly in the sports that we play in Ireland, the ball tends to be above the eye line so you tend to be focusing on the ball and catching it and then an opponent is tackling you, or you try to evade them so your eye line and your ability to move quickly can change.

Q: So what are we talking about here GAA, Hurling, Rugby and maybe Soccer as well?

BD: Yes Soccer actually has a very high basis of ACL injury, so all these kinds of ‘pivoting’ sports as we referred to already and really they make up the majority of team sports we play in Ireland.

BD: Yes, and it is hard to get a really good number on the injuries. A lot of countries, particularly in Europe and New Zealand, have registries where we can look and get a good idea of the number of people who are injured.

So we have different sports that run data surveillance like GAA and rugby, so we can get a picture of how common the injury is. Certainly, our levels would be equivalent to the likes of Australia, where they play similar types of sport.

BD: So it all depends on the age of the patient, really, people that are slightly older, maybe in their forties perhaps, we can treat these injuries non-operatively.

But for young patients, we tend to recommend ACL Reconstruction, particularly if they have any other damage within their knee.

The idea is you need to control the rotation in the knee and give that patient a stable knee. So we can’t repair them; they tried doing that in the past with very dubious results.

So now we have to reconstruct the ligament by tacking a graph typically from the patient themselves.

Q: That sounds like quite an involved treatment, quite a serious surgery?

BD: It is a serious surgery, we have refined the surgery over the years, so it is not the career-threatening injury it used to be.

Our techniques and our ability to diagnose ACL injuries have certainly improved and nowadays, it is a pretty routine surgery for us.

The prognosis for the patient or how they are going to do in the future is not just based on their injury of the ACL but also to the other important structures that are in the knee, such as the cartilage or shock absorbers which we refer to as the meniscus. This really determines how a patient does in the long term.

Q: There is also an increase in women being diagnosed with ACL injuries, I know we were doing a programme a couple of months ago on this and it is partly linked to the footwear women have been wearing, because the footwear woman wears in sports is designed for men and doesn’t take into account the different weight of women. etc., and the different ways they move.

Is that something you will be seeing as well, women are playing more sports also and women are being diagnosed with more ACL injuries?

BD: Yes, I think it is a multifactorial reason as to why women tend to create quite a risk in certain sports, but what we are certainly seeing is a greater level of participation of women, so therefore, we are seeing the rates increase in terms of the number of women presenting to us for reconstruction, definitely increases.

I think there was a very worrying trend in Australia, where I was working for the last eight years, where they have seen a huge epidemic of ACL injuries, particularly in the young female population, from the ages of twelve right up until eighteen.

I think similarly in Ireland we have more organised sports at a young age, particularly for girls and young women. Therefore our rates are increasing

BD: Well, the great thing is a lot of the sporting bodies that I have mentioned have fantastic initiatives in place to try to reduce the rates of injuries. I think initially they are referred to as injury prevention strategies, but really, we can’t prevent injuries but just reduce the risk.

These warm-up exercises have been shown to reduce the rate of injuries by up to fifty per cent, and they are included as part of a warm-up in GAA fifteen, FIFA Eleven and Rugby have an equivalent warm-up technique.

If you’re to do anything, it is to encourage your children and also their coaches to get involved in this warm-up because they are really very effective.

Q: Ok, so the warm-up really matters then? It’s really important?

BD: Absolutely, it matters.

Q: Is it something that children have a bit more resilience against? they are a bit more bouncy to use a non-medical term.

BD: They can be bouncy at younger ages, but what we typically see is when they become less bouncy as they get to the adolescent stage, they are probably at increased risk.

Also, once they have had ACL surgery, there is quite a risk of re-injuring the same ACL even though they have been reconstructed but also injuring the contralateral or opposite leg.

This is a group we really focus on. We refer to them as high-risk groups, so whereas we can try to mitigate and reduce the rates of injury when we have patients that have sustained these injuries, we have to think quite clearly in terms of how we reconstruct them and if it is efficient alone to do an ACL reconstruction or do we have to do something else to try to reduce the rates after surgery.

Alright, it was great speaking to you that was Brian Devitt, Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon at the UPMC Sports Surgery Clinic in Santry.